There's a wonderful book called The Great Good Place by Ray Oldenburg. He writes about "third places" -- informal gathering places that make "good towns and great cities". A particularly interesting type is the German-American beer garden that was once very common in New York, Chicago, Cincinnati, and Milwaukee (his examples). Our Friday Night Suppers seem to share some of the qualities he describes there...

The Great Good Place, Ray Oldenburg, 338pp, Paragon House, New York, 1989

The Great Good Place by Ray Oldenburg: Chapter 5

The German-American Lager Beer Gardens

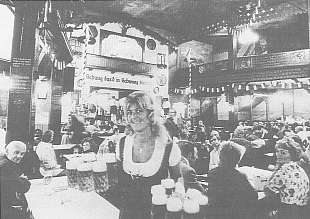

The expansiveness of this German beer hall

signals its welcome to one and all

"SOCIAL LIFE TODAY," wrote the Wisconsin historian Fred Holmes, "offers few meeting places like the old German saloon. Compared with it, the modern tavern is an arrogant pretender." In their saloons and even more so in their lager beer gardens, the immigrants from Germany set an example of controlling the use of the alcoholic beverage and literally building communities around its tempered use. Our history records no finer example of the successful third place than the German-American lager beer garden. In reflecting upon it, I recall that the man who wrote that "nothing is more hopeless than a scheme of merriment" was an Englishman and not a German. The German immigrant had the formula for merriment. It was so successful that it could b~ implemented daily without danger, disruption, or risk of failure.

The character of the lager beer garden grew out of a combination of factors. Among these, the demographics of immigration played an important part. German immigration, particularly after 1840, was as diverse as it was extensive. It was not dominated by a laboring class or any other social strata. Many "walks of life" had to be incorporated and unified into the communities established in the new land. At their basic, informal, and most pervasive levels, the sociable gathering places of these new Americans were inclusive.

The old-world traditions that the immigrants brought with them also played a vital role. In the main, they were those of a broad, urban middle class brought up in the enlightenment cities of Germany-a tradition with rich patterns of associational life. The lager beer garden was imported, as were the turnen or gymnastic clubs, shooting clubs, singing societies, chess clubs, drama clubs, fraternities, intellectual, cultural, and educational societies, and all manner of voluntary associations.

Beyond the chemistry inherent in the flow of immigrants and the traditions they brought with them were two important aspects of the life-view of the Germans that governed their collective behavior. These were a passion for order and the realization that informal socializing lay at the base of a viable community life. The lager beer garden became the parent form of association out of which the more formally organized activities would emerge. In order for the beer garden to play this important role, it had to have a unifying effect and never a disruptive one. It is not surprising, then, that the typical Yankee saloon left a great deal to be desired.

A German immigrant to Milwaukee described the latter in a letter to relatives in the Old Country written in 1846: "You can't stand around," he complained, "you get neither a bench nor chair, just drink your schnapps and then gO."3 There were other things amiss. The Yankees had the dangerous habit of buying rounds or treating. Treating may have posed a threat to the frugal German's pocketbook, but more than that, it threatened order. It undermined control over alcoholic intake, for among those buying rounds for one another it is the fastest drinker who sets the pace. All others are pressed to drink at a rate exceeding their personal inclinations. Against this habit, the Germans would establish the "Dutch treat" or the habit of each paying for his own beer and ordering at a pace controlled by the individual drinker.

In the Yankee saloon, the drinks were too strong. The English and Welsh had established the first breweries, but their products were much too potent. In the Irish saloons whiskey was the staple, behavior was rough, and those were anything but family places. Wherever the Germans settled in number and the locale was suitable for the growing of hops, there emerged German breweries and, shortly thereafter, a profusion of German saloons and lager beer gardens. Against the romanticized notion that the Germans, above all, demand fine-tasting beer is the historic fact that they paid even more attention to its alcoholic content.

That the Germans valued reduced potency above taste was amply attested to by Junius Browne, who wrote of the lager beer gardens in New York City in the 1870s: "The question, 'Will lager beer intoxicate?' first arose, I believe, on this island, "and, very naturally, too, considering the quality of the manufactured article. I have sometimes wondered, however, could there be any question about it, so inferior in every respect is the beer made and sold in the Metropolis. It is undoubtedly the worst in the United States-weak, insipid, unwholesome, and unpalatable; but incapable of intoxication, I should judge, even if a man could hold enough to float the Dunderberg. It is impossible to get a good glass of beer in New York, and persons who have not drunk it in the West have no idea what poor stuff is here called by the name. "

Alvin Harlow's account of Cincinnati during the same period suggests that the quality of the beer improved as one went west: "Some old-timers will tell you that John Hauch brewed the best beer in Cincinnati in the long ago, and he ,was as particular as any vintner of Rheims or Epernay as to his processes and handling. Along with many other connoisseurs, he shook his head when beer began to be bottled in the '70s; beer should always be kept in wood. He demanded that saloonkeepers who handled his beer should keep it in cellar coolness and handle it gently. His drivers were not permitted to drag a keg off the wagon and let it thump down on a pad on the sidewalk; it must be lifted carefully and lowered into the cellar with equal care."

The Germans clearly held standards of taste with respect to their national beverage. The sorry state of early New York beer, drunk under the pretense that it was good, as Browne suggested, serves only to show the greater importance they attached to temperance in drinking, Bad as early New York beer might have been, they would not turn to the "strong stuff. " The attitude was exemplified in Harlow's account of the goings-on during Cincinnati's fest of the Sangerbund in the summer of 1856: "In the afternoon we noticed a few cases of exhilaration, but none of that brutal intoxication which is too common in large gatherings of the Anglo-Saxon race. The comparatively unstirnulating beverages in which they indulge has something to do with this, but the practice of taking all ages and sexes to these meetings has more. It should be said that nothing stronger than beer might be sold at German outings. Once, when an outsider tried stealthily to purvey hard liquor, his bottles were seized and broken by the managers."

The lessons on drinking had been learned and refined into tradition in the Old Country and their importance was evident to the objective traveler. One such was the Englishwoman Violet Hunt, who contrasted public drinking establishments in Germany with those of her native England around the turn of the century. Her descriptions abundantly suggest what the German-Americans sought to establish across the Atlantic: "ona certain summer afternoon a troop of orderly, sober, decent, suave, and gentle persons of all ages and sexes were sitting on freshly-raked gravel, at little tables covered all with red-chequered table-cloths and coffee-cups and glasses on them. Their children sat beside them, and their dogs crouched at their feet or circulated about the feet of other clients. Birds hopped about under the tables, picking up crumbs which these gentle people from time to time cast to them. There they sat, stolidly, composedly, as if butter wouldn't melt in their mouths, gulping down grosse Hellers and kleiner Dunklers, and more and more of them, with no diminution of their holy calm. Their dogs did not quarrel, the birds still hopped about their toes in utter confidence; everyone was sure that no chairs would be hurriedly pushed aside or angry words flout the sweet air tht:y were taking in, amid smoke of cigars or pipes, and the soft breath of human converse. And discreet wives, with their children of all ages to think about, kept an eye on the sun and saw that it was declining. When they thought it was time, they folded up their fancy work, wrapped up the remainder of their buns, shook the crumbs off their children's bibs and folded them up likewise, and turned their eyes westward to where the gilded spires of Hildesheim seem to point them to their homes. Then men got up and shook themselves, and paid. There was in them plenty of beer, but not the least bit of harm in the world. "

Ms. Hunt, after observing this demonstration of humankind's mastery over demon drink, leapt to the announcement that it couldn't happen in England. There, she said, such ugly sights and sounds would follow two hours of drinking that the government would find justification for barring children from such places. In her native England, with all its "strenuous temperance and protective liquor laws" there were no places comparable to the German beer garden: "Any place of call in England which permitted itself to be as attractive as any of these would undoubtedly lose its license. Government morality would soon be on its hind legs at once lest vice should masquerade as health, joy as beauty. It carefully penalizes joy and merry-making by the enforcement of due ugliness in every place where this habit is permitted to be indulged. "

Much of the difference, Ms. Hunt insisted, was due to the drink: "German beer is not in the least like, in strength, in quality, or matur- ing, to the stuff which notoriously wrecks the Englishman's peace of mind, his pocket, and his home. It is not heady, it is diluted; it is not drugged or doctored, and it is kept properly. "

Junius Browne also observed the German festive tradition in all its implications from his vantage points among the innumerable lager beer gardens of old New York: "The drinking of the Germans … is free from the vices of Americans. The Germans indulge in their lager rationally, even when they seem to carry indulgence to excess. They do not squander their means; they do not waste their time; they do not quarrel; they do not fight; they do not ruin their own hopes and the happiness of those who love them, as do we of hotter blood, finer fibre, and intenser organism. They take lager as we do oxygen into our lungs-appearing to live and thrive upon it. Beer is one of the social virtues; Gambrinus a patron saint of every family-the protecting deity of every well-regulated household. The Germans combine domesticity with their dissipation-it is that to them literally-taking with them to the saloon or garden their wives and sisters and sweet- hearts, often their children, who are a check to any excesses or impropriety, and with whom they depart at a seemly hour, overflowing with beer and bonhommie, possessed of those two indispensables of peace- an easy mind and a perfect digestion. "

The passion for order conquered alcohol and its use. Yet, for the saloon and beer garden to become an integral part of community life, cost also had to be controlled. The Yankee proprietor and host has always had a keen sense of his fellow citizen's needs for release and diversion and had a knack for capitalizing on it. The German- American, on the other hand, demanded public places where costs were low and loitering and idleness were encouraged. Only if those conditions obtained could the saloon and beer garden become the universal gathering places of the citizenry.

The success of the German-American places caught Browne's attention as he observed New York's Bowery area in its finer days: "With all their industry, and economy, and thrift, the Germans find ample leisure to enjoy themselves, and at little cost. Their pleasures are never expensive. They can obtain more for $1 than an American for $10, and can, and do, grow rich upon what our people throwaway. " German effectiveness in holding down the cost of public enjoyment was also noted by Holmes in the Milwaukee scene: "Throughout the Gay Nine- ties beer was cheap, the tax on it being negligible. Indeed, it was not until 1944 that the five-cent glass of beer became scarce in Milwaukee. During the late nineties there were four saloons on the southwest corner of State and Third Streets which sold two beers for a nickel and provided an elaborate free lunch of roast beef, baked ham, sausage, baked beans, vegetables, salads, bread and butter, and other appetizing foods. Two men with but a nickel between them could each enjoy a substantial meal and a mammoth beer." Holmes also pointed to the larger implications: "The early Poor Man's Club solved an important social-economic problem. In a time when capital was needed for the building of homes and the promotion of commercial and industrial activities, it provided recreation and social intercourse for almost nothing. "

The German immigrants well understood that informal public gathering places were too important to the life of the community to cripple them by prohibitive pricing. Kathleen Conzen's accounts of Milwaukee's establishments are similar to those of Holmes: "By 1860 the best of Milwaukee's taverns offered beer that was both good and cheap, food which was often free, stimulating conversation, music, perhaps a singing host. ...The first of Milwaukee's many outdoor beer gardens opened on the northeast side near the river in the summer of 1843. It offered 'well-cultivated flowers, extensive promenades, rustic bowers, and a beautiful view from Tivoli Hill,' as well as a German brass band providing music one afternoon and evening a week, all for a 25cent admission fee."

Nowadays, the term lese majesty, or treason, invokes an image of someone selling secrets to the Russians. German-American immigrants, however, had a much keener and broader sense of it. To them, the manager who overcharged for a public concert or the "roughs" who destroyed a picnic by fighting were engaging in treason as well. Any- thing that threatened the tranquility and full enjoyment of community life alerted their sensibilities. To them, the social order declined, as Richard O'Connor astutely observed, not by major rifts at its core, but by disorders tolerated at the fringes. 15 To them, the enemy spy and the ticket scalper were of the same ilk. A low and permissive cost for the public consumption of food, drink, and music (primarily) was essential to community and the establishment of solid relations with neighbors.

Orderly behavior and minimal expense were crucial to the ultimate inclusiveness and accommodation of the beer gardens. Everyone had to be allowed to participate lest those places fail in their purpose. The lager beer gardens were there for the children, women, and non- Germans also, and social class was largely forgotten. What was strictly German or could not be shared with outsiders was protected within the family. As Richard O'Connor put it: "In their homes, the Germans tended to keep the family circle, but when the bungs were tapped out and the wine uncorked all nationalities were invited to join in the singing, dancing, drinking, and feasting."

In the Atlantic Garden, which had been one of New York's most celebrated beer gardens, inclusiveness was the essence. Browne reports: "The Atlantic is the most cosmopolitan place of entertainment in the City; for, though the greater part of its patrons are Germans, every other nationality is represented there. French, Irish, Spaniards, Italians, Portuguese, even Chinamen and Indians, may be seen through the violet atmosphere of the famous Atlantic. …" The Atlantic was a grand pavilion capable of holding twenty-five hundred people. It was the best the immigrant Germans could offer-and they offered it to one and all.

Inclusiveness was central to the coveted atmosphere of the lager beer garden. It was a garden in a double sense-in addition to the greenery, human relationships and goodwill were cultivated. The atmosphere in which this is accomplished most effectively has a name well understood in the German language. It is Gemütlichkeit. What is Gemütlich is warm and friendly. It is cozy and inviting. Of all the failings of the Yankee saloon, its lack of Gemütlichkeit was undoubtedly the greatest. Such places were for the brawlers and those determined to get drunk, but not for a man and his family nor for those who measured their enjoyment by the pleasure on others' faces.

True Gemütlichkeit, an atmosphere in which community and neighborliness is realized and celebrated, could not be based upon exclusion. It could not shut out ages, sexes, classes, or nationalities. By its nature, it must include them and, this above all, the lager beer gardens managed. A German in Cincinnati, for example, might prosper and buy a house "up on the hill," but, as Harlow records: "such people did not disassociate themselves from their fellow countrymen in the Trans-Rhenish area, as downtown newspapers liked to call it; they returned there to the beer halls and restaurants, the numerous clubs and societies-political, literary, musical, athletic-for their relaxation and exercise."

Harlow also records an incident in which a visiting professor from Harvard was introduced to beer garden Gemütlichkeit by a friend: "With Escher, I found my way to the society of Germans in Cincinnati, a most interesting group of men, from whom I had much enlargement. Some of the ablest of these men were accustomed to meet at a beer hall in the part of town north of the canal. There were many of these men of quality. ...These were strong men; their talk made a great impression on me and their personal quality did much to lift me to a higher level of ideals than any of our people supplied. "

The frequent discovery of native Americans that there were those in their midst who could create places in which the divisions of the mundane world were overcome was indeed heady stuff. Harlow quotes a Cincinnati reporter who had been invited to a party given by the German Workman's Society in 1869: "The fellowship was contagious; everybody was affected by it. We must not omit the children, from babies up to men in second childhood. Little girls, as many as wanted to dance among the elders, looked for all the world like grown people seen through a spy-glass with the big end to the eye. Everybody was intent upon making everybody else as happy as could be. We commend this example to other people, not better, but more pretentious."

Another newspaper man was present at a German concert and wrote of the socializing that followed: "The air is comforting with the fra- grance of hops, coffee, and tobacco. Combined with the music of Suppe and Strauss it induces a benign expansiveness in which one feels like taking the world to one's bosom, even including Old Petrus Grimm, who sits alone at a table with his dour eyes fastened on his beer mug. Petrus is the neighborhood bear, and everybody b!a~es his bitterness on a blighted troth in the Old Country, though It IS more likely due to liver and gout. "

The inclusiveness at the core of Gemütlichkeit was duly noted by Fred Holmes, who sought to correct the error made when people referred to Wisconsin's lager beer saloons as "poor man's clubs": "the term Poor Man's Club is something of a misnomer, for the saloon attracted not only the daily worker, but his employer and the business and professional men of the community, many of whom were men with wealth. What the term implied, of course, was that the saloon's clientele was not drawn from the highbrow or social-register class. ...The Poor Man's Club was born of men's desire, conscious or unconscious, for friendly relations with their neighbors. It existed without formal organization, recorded membership, officers, or funds for planned activities. No class cleavages were recognized, characteristic as these were of German society. ..in the popular gathering places-the Schlitz Palm Garden, Schlitz Park, the Milwaukee Garden, Heiser's-the measuring stick of wealth and family prestige was not applied. Rich and poor, artist and laborer, scholar and illiterate all mingled as a single family united by the bonds of homeland and community tastes. "

The inclusive or "leveling" character of the lager beer garden was most obvious in the more palatial establishments. Holmes provides a description of the world-famous Schlitz Palm Garden, the most notable indoor "palm gardens. "23 Boasting high, vaulted ceilings, stained- glass windows, rich oil paintings, a pipe organ, and lush palms throughout, it, too, was a "poor man's club." It was policy to make the poor feel as welcome as the rich; social distinctions were not compatible with Gemütlichkeit.

The splendor of the place and the quality of the entertainment it provided were not seen as cause for raising prices. Thirty to fifty barrels of beer were dispensed at five cents a glass daily, and free lunches, as in any other saloon in Milwaukee at that time, were standard fare. Concerts were conducted on Sunday and everyone was welcome.

The mixing of nationalities, presence of women, comingling of the rich and poor, and frequent instances in which three generations had fun together at the same time and in the same place-these were the more striking signs of inclusiveness. There are other dimensions of inclusiveness, however, and these include the availability of public gathering places and the general frequency of their use. On both counts, the phenomenon of the lager beer garden was extensive.

Browne estimated that Manhattan alone had three to four thousand lager beer gardens, "not to mention their superabundance in Jersey-City, Hoboken, Brooklyn, Hudson-City, Weehawken, and every other point within easy striking distance of the Metropolis by rail and steam. "25 And the pattern of profuse growth was similar in Buffalo, Cincinnati, Milwaukee (dubbed the Haupstadt of Gemütlichkeit), St. Louis, Chicago, and outer San Francisco.

As Browne observed: "These establishments are of all sizes and kinds, from the little hole in the corner, with one table and two chairs, to such extensive concerns as the Atlantic Garden, in the Bowery, and Hamilton and Lyon Parks, in the vicinity of Harlem."

A lager beer garden differs from a saloon in that the latter has a lengthy bar or bar-counter, which constitutes its focal point of sociable gathering, while in the former tables and chairs are prominent. The term garden came into vogue because of the German preference for the summertime version of the beer-drinking institution. Beer, apparently, "went best" with music and fresh air. In many respects, the colossal structures such as the German Winter Garden and the Atlantic Garden were attempts to capture the expansiveness of the out-of-doors park in the cold of winter. In the majority of places, perhaps, reality strained the concept of a garden. In surveying the range of places that went by the name in nineteenth-century New York, Browne concluded that "The difference between a lager-beer saloon and a lager-beer garden among our German fellow citizens is very slight; the garden, for the most part, being a creation of the brain. To the Teutonic fancy, a hole in the roof, a fir-tree in a tub, and a sickly vine or two in a box, creeping feebly upward unto death, constitute a garden."

The large and elegant gardens of the day may be viewed as the precursors of America's contemporary theme parks. Atlantic Garden had, for example, an enormous front bar and many smaller ones. But it also contained a shooting gallery, billiards rooms, bowling alleys, an orchestrion which played daily, and multiple bands which played in the evenings. Many people attended nightly. The outdoor parks of Milwaukee supplied a similar diversity of entertainment. These offered many pavilions and picnic areas, carousels, and long, open-air tables scattered everywhere. Pabst Park sported a fifteen-hundred-foot roller coaster, a Katzenjammer Fun Palace, Wild West shows, and daily concerts during the summer season. Schlitz Park occupied eight acres atop a local Milwaukee hill and had a large pagoda from which visitors could see the entire city. It offered a concert hall with a capacity of five thousand, a menagerie, winter dance hall, bowling alleys, and a large restaurant. Interspersed throughout were shady walks, fountains, and flower beds. At night, thirty-two electric lights, five hundred colored glass globes, and thousands of gas flames lent "grand splendor" to the whole place. Admittance was usually twenty-five cents, which was not a small amount of money for many in those days. The fee was necessary to compensate for the large number of freeloaders those parks attracted.

Many nations of the Old World contributed large numbers to the immigrant flow that peopled the United States, but few among the diverse nationalities actively promoted forms of sociable ethnic mixing essential to the democratic "melting pot." The Jews were consistent antiassimilationists, and the Greeks confined public socializing largely to their own coffee shops. The Scandinavians, Italians, and Poles catered to their own kind, and only the Irish and Germans emerged as "universalists," along with some older Americans no longer reliant upon ethnic ties.29 The difference between the Irish bar and the German beer garden as focal points of public gathering and interethnic mixing, however, was almost literally the difference between day and night. Whereas "the Irish bar tended to be dimly illuminated, the lighting in the German place was as bright as daylight," and the "German saloon was as much a family institution as the Irish bar was a man's world."3° Though unescorted women were not welcome in the German places, the entire family was, children included. German saloons and beer gardens typically escaped the chronic American indictment against the barroom. Extremely little crime was associated with them. In fact, German saloonkeepers were often trusted above banks for the safekeeping of one's savings. Even its critics had to admit that the German saloon had a stabilizing influence on the family.

Yet it was the Irish model that eventually prevailed. America adapted itself only to the German national beverage; it kept the beer and dropped most of the amenities with which the Germans had surrounded it. The nation never seemed able to allow the concept of a good tavern, and people who cannot envisage good taverns are doomed to have lesser ones.

Perhaps the most irksome aspect of lager beer gardens and the German saloons was that they were most appreciated, enjoyed, and populated on Sundays. From the culture of the enlightenment cities, the German immigrants brought with them the institution of the "Continental" Sunday. Germans were accustomed to finding their relaxation and the restoration of their soul in the form of picnic outings, concerts, scheutzen fests, gymnastics, choral singing and, above all, the rich and boisterous association afforded by the lager beer establishments. The serenity of the German's life-style depended in large mea- sure upon such forms of relaxation; the German riots, such as occurred in Chicago, stemmed from attempts to shut down typical Sunday activities. Unfortunately, the dominant modes of religious thought in America imposed idleness apart from work, particularly on Sundays.

A German newspaper editor, Karl Griesinger, spent several years in America during those critical times. He was appalled by the boredom and idleness of the Yankee Sundays and discerned a simple economic motive beneath all the righteous ranting about "keeping the Sabbath. " American churches were not built by government or any form of taxation. They depended upon voluntary giving. Giving, in turn, depended upon attendance and membership. Average preachers were fighting for their lives as well as for God. Anything that competed with the church, particularly on Sundays, was threatening not only to the "kingdom" but also to the poor preacher's livelihood.

Griesinger's analysis was as clear as it was singular: "Clergymen in America must then defend themselves to the last, like other business- men; they must meet competition and build up a trade, and it's their own fault if their income is not large enough. Now is it clear why heaven and hell are moved to drive the people to the churches, and why attendance is more common here than anywhere else in the world? It is an element of high fashion and good manners, and woe unto him who takes a stand against manners and fashion. Better to commit a slight forgery than to miss a Sunday in church.

"But then, what else could the Americans do on the sacred Sunday? Boredom alone would bring them there! 'Six days shalt thou labor and on the seventh shalt thou rest. ' Reasonable men have understood this to mean that Sunday should be a day for the relaxation of body and soul. The Americans have arranged matters, however, so that the rest of Sunday is the rest of the tomb. And they have enacted laws that make this arrangement compulsory for all.

"On Sunday no train moves, except for the most essential official business; no omnibus is in service, no steamer when it possibly can help it. All business places are closed, and restaurants may not open under threat of severe penalties. A gravelike quiet must prevail, says the law, and you may buy neither bread, nor milk, nor cigars, without violating the law. Theaters, bowling alleys, pleasant excursions-God keep you from ever dreaming such things! Be grateful that you are allowed in winter to build a fire and cook a warm supper. People who make such laws must be half crazy!"

History, Griesinger would have been pleased to know, bore him out. Most American churches now sponsor sociable activities for the same reason they once prohibited them, even on Sunday! It is difficult to judge the ultimate effect on the character of Americans of religious views that denied the opportunity to balance competitive relations with those allowing a spirited and joyful association with their fellow crea- tures. German-Americans, however, held fast against the conditions that produced the dourness of the typical Yankee. They did so, at least, until time ran out. Eventually the combination of W. C. T. U. morality, the bigotry of the Know Nothing party, two wars with Germany, and the willingness of German-Americans to assimilate relegated the lager beer garden and the life-style built around it to the past.

It is disheartening to observe the hollow forms and shoddy imitations of the lager beer garden Gemütlichkeit, which are about all that remain today. Some years back, we visited a Midwestern theme park. After paying an immodest parking fee, we were charged nine dollars each for the adults in the party and eight dollars for each child. Inasmuch as there was virtually nothing there for adults, it might have been appropriate to let them in free and give them a beer on the house for the trouble they had taken to transport the children to the park. The most common activity in the park is standing in line; everybody spends most of their time doing that. The beer garden offers one brand only; it's served in waxed-paper cups and is overpriced. On what appeared to be only a moderately busy day, we stood in line for half an hour to get our choice of a bratwurst or a hot dog. People don't go there nightly, as was the case with lager beer gardens of old. One visit per summer is enough for some; one every five years is adequate for others. But for many, I suspect, one visit in a lifetime is more than enough.

A few summers ago, an annual lodge picnic was held in one of the parks of a small city. It was spirited and well attended. Many who had been there said they had a great time, and they talked about it for days, even weeks, afterward. Within the context of that wonderful time, however, several things occurred that might give pause. There were injuries incurred during a softball game, including two broken bones. There were wives upset about the attention their husbands paid to other women. There were husbands upset about wives who reciprocated. For these and other reasons, many couples were not on good terms for quite awhile afterward. There were many bad hangovers the day following the picnic. Equipment and personal possessions were broken or lost. The food and drink consumed ran up a formidable bill.

One may surmise that those folks weren't civilized, or contrarily, that they had a pretty good time. It may appear that they were overdue for such an outing and, understandably, went overboard when the chance for celebration finally came. Those are speculations, but what is clear beyond speculation is that a gathering of that kind cannot take place often. The bodies can't afford it. The pocketbooks can't afford it. The marriages can't afford it. By way of contrast, the controlled and inexpensive revelry of the lager beer gardens-all those good times at little expense and no disruption-meant that they could be indulged frequently. And they were. The German-Americans, in addition to in- venting innumerable excuses for their own fests, helped the Italians honor Orsini with parade and feast and made a bigger deal of Washing- ton's Birthday and the Fourth of July than the native Yankee.

In Dixie, there's a small community originally settled by German- American farmers. In recent years, and with the uncritical assistance of area newspapers, the locals have been sponsoring a sausage festival. Thousands descend upon the little hamlet, beckoned by a nostalgic spirit, to enjoy an old-style German fest. What sounds from afar like a little German band is, alas, a record played over and over through a public address system. There is no band and there are no costumes. The central area of the celebration is taken up for the most part with booths and tables at which locals offer garage sale items at retail store prices. Among them are few real collectibles and absolutely no deals. Center-stage is dominated by those too poor or timid to become genuine retailers and who hope to peddle their junk to those in a festive mood.

Local craft-hobbiests hawk amateurish pottery, useless objects made of wood and glistening with heavy layers of epoxy, and garish crochet work. There is a petting zoo for the children. Fortunately, as it turns out, it is not free, and the cost of admission is sufficient to keep many children away. Later in the afternoon and early evening, many parents take their children for medical attention for the bites by the fleas, lice, and ticks, which cover the animals.

The beer is not easy to get. One stands in line for tickets and then in another line to trade the tickets in for beer. The beer is served in waxed cups, and the prices are inflated. The food is passable but short of "lip smackin'." To get a plate of it, one stands in line for nearly an hour. All along the streets leading to the festival area are garage and yard sales. Where once small-town America took pride in playing host at its annual celebrations, there is now a new attitude. An ever-increasing number of townsfolk preoccupy themselves with how to get their share of the money involved.

The assessment of this sausage festival would be misleading if I failed to point out that it continues to be a success in terms of its repeated ability to draw crowds. Why? Several factors seem to account for the unmerited popularity of the festival. Most of the visitors, and particularly those under fifty years of age, have only those powers of discernment that experience has provided. Bluntly put, they have not witnessed better community festivities organized at the grass-roots level. Parking is free and there is no staggering admittance charge, as confronts the visitor to the theme parks, World's Fair, or Disney Kingdoms. Many undoubtedly find the event a welcome contrast to the slickness of the corporately-managed theme parks in which people are moved, stacked, and set in line with all due efficiency.

I have indulged in a few comparisons in order to emphasize what America lost in rejecting the example of the lager beer gardens. Ulti- mately, however, it is not appropriate to compare a contrivance with an institution. It is not accurate to compare an annual oddity, such as the sausage festival, with lager beer gardens, which were once an integral part of a prevailing life-style. An occasional celebration, no matter how well planned, cannot offer what accrues from regular association and participation.

The German-American lager beer garden represents the model, par excellence, of the third place. It was the bedrock for informal and encompassing social participation out of which friendships were formed and interests were matched. Those who came to meet and know one another in the happy informality of the beer gardens went on to form drama clubs, turnen, debating societies, singing groups, rifle clubs, home guards, volunteer fire departments, fraternities, and associations dedicated to social refinement. It was the basis of community. Though organized around drinking, it was, as O'Connor observed, ''as respectable as the corner grocery store." Unlike the Yankee saloon, which inspired so many temperance hymns and which promoted the image of Little Nel vainly searching for her father amid a throng of drunken barroom revelers, the beer garden was a unifying force in family life, not a divisive one. The beer garden balanced the competition of the American economic system with steady doses of fraternity; it balanced the inequalities of social life by welcoming all to its circle of amenities on an equal basis. The German-American seemed to know, more than others, the imperatives of people's basic social nature-for one to be happy, others must be happy too. They set the tripod of the first, second, and third places on rough new terrain. Doing so lent stability to their lives and civility to the neighborhoods in which they settled.

The Great Good Place, Ray Oldenburg, 338pp, Paragon House, New York, 1989